About

Purpose

The recordings in this collection are of Tlingit speakers talking naturally to each other in their ancestral language. From 2007 to 2013 Tlingit elders made the recordings for current and future Tlingit language learners. We hope the recordings and subtitles will help learners hear, understand, pronounce, read, and write Tlingit. We hope the content of these conversations will be of value to the Tlingit community and others for the history, stories, child rearing, fishing, women’s ways, men’s ways, humor, games, songs, Tlingit protocols, food harvesting and preparation, flora, fauna, kin relationships, weather, land ownership, potlatches, medicine, funerals, and more.

We also hope these recordings will be of value to Linguists, the scientists who study all aspects of Language, asking questions such as: What sounds are used in the language? What combinations of sound contain meaning? How are words formed? How are words organized into longer units of meaning? Do women speak differently than men? How is this language acquired? What languages are most similar to this language?

This has been, all along, a guilt-free, apology-free, grief-free, complaint-free, shame-free project. Each recording presented here is imbued with the joy and healing we all felt in working with it. We wish you joy and wellbeing as you use these materials and hope they benefit you on your pathway, whatever it may be.

Nearly everyone who listens to these recordings hears something new that others have missed. We welcome your suggestions for improvement and will incorporate them into the written captions, with your name if you wish. Email your suggestions to alicetaff@gmail.com.

Funding

Woosh Een áyá Yoo X’atudliátk was funded by 3 generous awards from the National Science Foundation/National Endowment for the Humanities – Documenting Endangered Languages initiative (DEL). The first award, in 2007, #0651787, was a pilot project to record and format 2 hours of Tlingit conversation. The second award, in 2009, #0853788, was a major project to record and format 30 hours of Tlingit conversation. Funding for #0853788 came to DEL under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-5). The third award, in 2019, #266286-19 was a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to Alice Taff to complete the transcription and translations of the 48.5 hours of video recordings that weren't completed under the first 2 projects. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

We are grateful to the vision and actions of the many people who made it possible for us to do this work with and for the Tlingit nation, a nation within 2 nations, and others who use these recordings.

Project Goals

Under the grants, our goals were to:

- Video record unscripted Tlingit conversation among the most fluent speakers. We recorded 48.5 hours among 60 elders in 10 locations.

- Broadly translate the video recordings to English.

- Transcribe 15 hours of the video recordings in the Tlingit writing system.

- Make subtitled videos accessible to the Tlingit language community, the scientific community, and the general public. The subtitled videos were accessible until Flash deprecation made the subtitling software unuseable. We are working to make subtitled videos available again.

- Keep detailed information on all the recordings and their workflow. Information about each recording is in the Woosh Een áyá Yoo X’atudliátk Video Catalog.

- Securely archive the project results. The electronic materials are archived at the Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau, AK, and at the Alaska Native Language Archives, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- Broaden the participation of underrepresented groups by developing a cadre of Tlingit language community members with increased Tlingit language and literacy skills, knowledge of linguistic concepts, and knowledge and experience in best-practices for endangered language documentation and archiving. On the website, select Speakers who Recorded and People who Assisted for the names of project participants.

Recording

Documentation vs. Documentary

These recordings are “raw data”; they are unedited unless otherwise noted. They are “documentation” as opposed to “documentary”.

We think of a “documentary” as a film that tells a certain story. A documentary film is typically shot over a relatively long period of time then is highly edited to present the essence of the story in a 90 minute sitting.

Our documentation process is almost the opposite. The most fluent Tlingit speakers available met in small groups, usually pairs, and talked about whatever they wanted. The recordings you see here start when the camera is turned on and end when the camera is turned off. It will take 40 hours to watch all these recordings once.

Our typical recording session took place in the home of a speaker, bringing in another speaker for conversation. The recording team, from 1 to 5 people, settled the speakers comfortably, set up lights, camera, and microphones, turned off any extra noises like TV, radio, refrigerator, furnace, clock. They read the project protocol forms to the speakers. When the speakers wanted, the camera was turned on or off. It isn’t easy to behave naturally when a camera is staring you in the eye. The speakers have presented a precious gift to us with their words. At the end of each recording session, usually less than an hour but sometimes more, we made sure all permission and payment forms were completely filled out and signed. Sometimes we arranged for another recording session or perhaps a translation session.

Besides homes, other recording locations were in community halls, housing for the recording team, outdoors, and schools. The team recorded in Yakutat, Klukwan, Juneau, Hoonah, Sitka, and Angoon, in Alaska, also in Atlin, Telsin, Carcross, and Whitehorse, Canada.

Recording Equipment

Usually we used our heavy equipment, a Sony 170 camera, recording on mini digital video tapes (miniDV) in DVcam format. Our backup camera was a Canon GL2. Sometimes recording opportunities were such that we used a smaller Canon Vixia HF R-20 camera with its built-in microphone. This camera recorded onto solid state or SD card (Secure Digital card). Once we used a Panasonic PV-GS150. Recording 2 speakers we usually used 2 remote lapel microphones. If there were more than 2 speakers, we used a single, table-mounted, cardioid microphone. Occasionally a camera-mounted shotgun mic came into play.

Post-Production

“Raw data” DVDs

As soon as possible after each recording session, ideally the same day, we transferred the recording to computer using iMovie then formatted the recording for DVD. We made and labeled several DVD copies, usually 5, one for each speaker and some extras for backup. Much of the time we were able to give DVDs to the speakers the day following their recording session.

English Translations, Tlingit Transcriptions and Subtitles

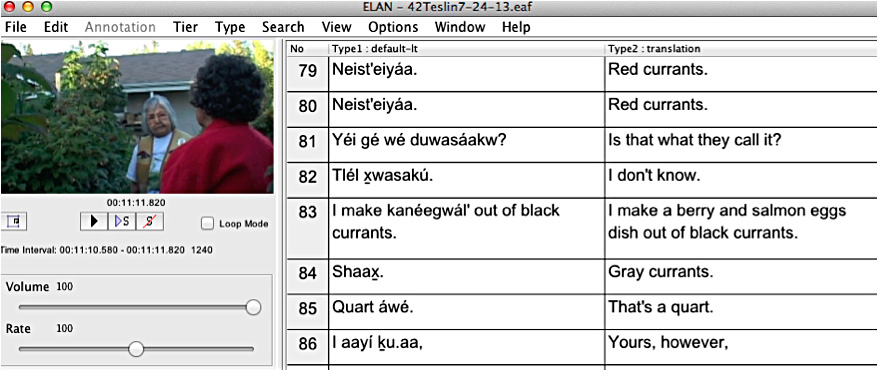

Teams of fluent Tlingit speaker and typist worked together to write out each recording in both Tlingit and English. Time-aligned text entry was accomplished using the software, ELAN (Versions 6.0 (2020) and 6.1 (2021)). Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive. Retrieved from https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan. ELAN plays sections of video and audio while users enter annotations as in the example below, lining up the written text with the video.

On average, it took 1 hour to translate to English 5 minutes of recording. On average, it took 1 hour to transcribe in Tlingit 1 minute of recording. All but one of the Tlingit transcribers available to work on the project are heritage second-language learners of Tlingit. They found it easier to transcribe what they were hearing on the recordings if the translation was already done and available to them. Therefore our first task was for one of them to sit with an elder, play a section of the recording, have the elder give the translation and enter it into ELAN. When the English translation was done, as in the column on the right above, a transcriber entered the Tlingit as in the column on the left above. Then another transcriber reviewed the translation and transcription, correcting errors.

For the most part, the text is divided into phrases by the speaker’s pauses. The translations are “broad”, that is, not word-for-word following the Tlingit. However, when it doesn’t distort the English beyond poetic acceptability, we tried to make English translations as literal as possible and follow the Tlingit word and phrase order.

The Tlingit transcriptions are written using the Coastal American Tlingit alphabet (as opposed to the Inland Canadian Tlingit alphabet). The Tlingit alphabet includes some underlined letters; x̱, x̱ʼ, x̱w, x̱ʼw, g̱, g̱w, ḵ, ḵʼ, ḵw, ḵʼw. The underline indicates that the sound is pronounced with the back of the tongue touching the uvula (hanging from the roof of the very back of the mouth).

Symbols in the Annotations

{ } We enclose false starts in curly brackets so that users will recognize that these are not words to learn; they are just speakers’ natural stumblings which are usually self-corrected. Everyone does this in conversation. Record yourself with your friends to test the truth of this statement.

( ) Parentheses enclose words that are added for clarity by the translator or transcriber. Most of these are in the English translations.

[ ] Square brackets enclose notes by a translator or transcriber.

??? Means that the writers can’t understand the speaker.

- A hyphen shows that a speaker stopped before the end of a word.

« » are Tlingit quotation marks. These marks are used for quotations in Tlingit instead of " so that they wonʼt be confused with one of the letters that combines with ʼ such as sʼ, tʼ...

Cataloging

Numbering the Recordings

The unique identifier for each recording is the number on the original recording tape. These are numbered in sequence as they were recorded, starting with mini DV tape 01, recorded on June 29, 2007, and ending with miniDV tape 96 recorded on May 19, 2013.

Each of our working files start with the tape number followed by some words to remind the team about the content of the tape, usually the names of the speakers or the location of the recording. Each file, in any format, refers by number back to its original recording tape. For example:

| Media Type | File Name |

|---|---|

| Original miniDV tape | Tlingit Conversation 16 |

| Working video file | 16WalterJohn.mov (Walter Soboleff and John Martin) |

| Working audio file | 16WalterJohn.wav |

| Working ELAN annotation file | 16WalterJohn.eaf |

| Working text file | 16WalterJohn.txt |

Notes on the Recordings

Information about the contents of each recording and its status in the workflow was kept in an Excel spreadsheet with the following column headings:

- Unique identifier

- Speaker 1 Tlingit/English Name, (moiety, clan, house, child of, ḵwáan, yádi)

- Speaker 1 birth year

- Speaker 2 Tlingit/English Name (moiety, clan, house, ḵwáan, yádi)

- Speaker 2 birth year

- Speaker 3 Tlingit/English Name (moiety, clan, house, ḵwáan, yádi)

- Speaker 3 birth year

- Language (tli, eng)

- Date of recording

- Location where recording was made

- Recorded by

- Original recording equipment

- Original recording format (for instance; MiniDVcam, SDcard)

- New formats

- DVD title of raw footage and # of ccs.

- Description of contents

- Notes

- Length of recording seconds

- Length of recording minutes

- Transcribed by

- Transcribed filename

- Transcribed seconds

- Translated by

- Translated filename

- Translated seconds

- Tlingit proofread by

- Tlingit Proofed file name

- Tlingit proofed seconds

- AT Reviewed

- Subtitles applied filename, worker name

- Seconds prepared for posting to web

- Subtitled item to web

- Subtitled item to distribute

- Archived at, as, date

- Rights

- Rights Holder

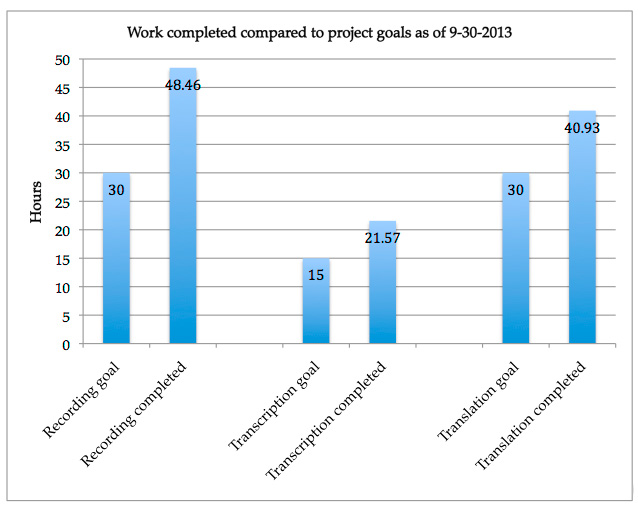

Keeping and totaling the seconds or minutes on the spreadsheet allowed us to track the amount of work we accomplished as we moved towards our project goals. Totals were graphed in an active chart as below:

Copyright & Archiving

Copyright

The speakers and the interviewer hold copyright to the videos. Those who have chosen to, have also transferred copyright to the University of Alaska Southeast for stipulated purposes. This transfer extends copyright to UAS but the speakers and interviewer retain their personal copyright title.

Archiving

All the materials for this project are housed electronically at the Sealaska Heritage Institute Archive in Juneau, AK and at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Alaska Native Languages Archive.